“Harm reduction is not what’s nice, it’s what works”

DPA founder Ethan Nadelmann

Changing behavior takes time, effort and community support. How do we, as fellow human beings, best support those who are engaging in risky drug behavior? Should Health Departments (and the nonprofits they contract with) distribute drug paraphernalia as a first resort, a last resort or not at all?

Is it a legitimate service for the government to provide tools for citizens to consume unregulated street drugs?

Or is it time to bolster them with different tools?

Before reversing course, in 2023 elected officials practicing their version of harm reduction in the Portland Metro area voted to distribute

“clean tin foil and straws for street drug users, particularly those who smoke fentanyl. In addition, the county Health Department said in a statement, it will be distributing “bubbles” and “stems” or glass pipes for people who smoke methamphetamine or crack, as well as “snorting kits” for those who inhale drugs.”

This is a sea change in the power center handing out drug kits. In the 1990s harm reduction began as an unsanctioned endeavor to limit the spread of HIV among existing IV drug users. Volunteers stood on designated street corners to accept one used needle in exchange for one fresh needle. It was rebellious and renegade: if the cops showed up, everybody scattered.

In Oregon, needle distribution is still the backbone of harm reduction, but now it’s woven into state law. Oregon drug overdose deaths grew 22% during a 12-month period ending in April 2024.

In 1999, DPA founder Ethan Nadelmann addressed a conference I attended with the opening remarks,

When we’re talking about drug education, harm reduction is your fallback strategy. What happens when “Just Say No” stops working?…What’s your fallback strategy? What are the “bicycle helmets” of drug education, and the “seat belts”?…Ultimately our bottom line, where it comes to drug education…isn’t about keeping our kids drug free. That is a means…towards and end, which is their safety — their growing up surviving the risks that they, mostly, inevitably will take, so that they grow up to be healthy, and thoughtful, and decent human beings.

In a later breakout session called Harm Reduction Around the World (I have a copy of the conference transcript) he further clarified:

There are many definitions of harm reduction, but there is a core definition. That core definition is that harm reduction refers to those approaches and interventions that seek to reduce the negative consequences of drug use among those people who cannot, or will not, refrain from using drugs today. That’s the basic, most common denominator…The harm reduction approach generally tends to say that whether or not drug use is going up or down, whether or not the number of people who admit to having used a drug, legal or illegal, went up or down last year — that’s an interesting question. It’s a relevant question. But, it’s not the most important question. Far more important is to ask the question: Did intervention X, policy Y, treatment Z succeed in reducing death, disease, crime and suffering associated with both drug use and the intervention itself? So that even if use when up somewhat, but death, disease, crime and suffering generally went down, that’s progress.

Takeaway 1: There will always be teenagers who experiment with drugs. Let’s be realistic and give teens the information to be as safe as possible while they try drugs so they can grow up and thrive as adults. In 1999, when experts thought ecstasy was the riskiest youth drug, this was reasonable! There weren’t synthetic opioids so poisonous that one pill can kill multiple people. It wasn’t customary for street drugs to be intentionally mislabeled and used to poison people instead of just getting them high.

Takeaway 2: The success of harm reduction isn’t related to less people using less drugs. Harm reduction is successful when DEATH, DISEASE, CRIME and SUFFERING related to drug use and drug prohibition have gone down. Can any Oregonian honestly say human suffering has decreased since drug access has increased? 25 years later, here’s the broken promise of harm reduction: drug use did go up, but SO DID death, disease, crime and suffering.

Takeaway 3: Harm reduction is a failure.

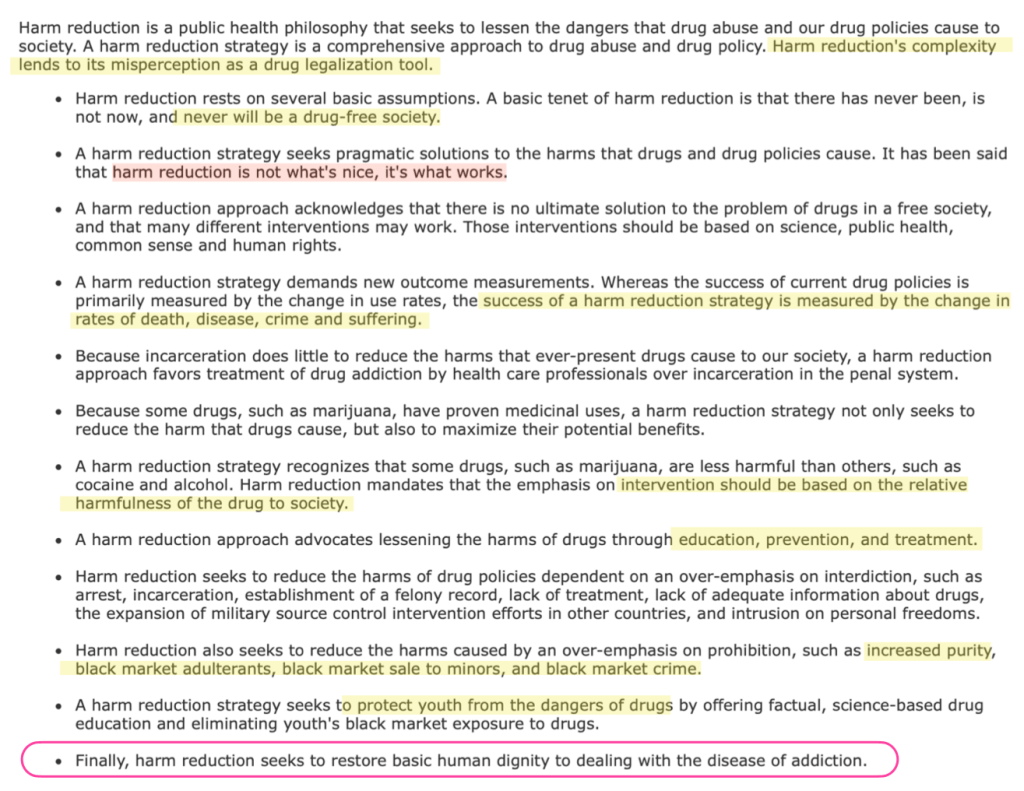

I’ve added highlights to an archived DPA website page from 2002. It’s an overview of harm reduction:

Are youth safer from the dangers of drugs than they were 25 years ago?

1 in 5 deaths in California for people between the ages of 15-24 are overdoses involving fentanyl.

Are street drugs safer than they were 25 years ago?

A person in San Francisco dies of an overdose every 10 hours.

Are education, prevention and treatment prioritized?

Has basic human dignity been restored?

What do you think?