Drug Policy alliance (DPA)

DPA was the first U.S. project of George Soros’ Open Society Institute. Their influence increasing drug access for Americans over the past quarter century can not be overstated. Before they were lobbying the government to declassify fentanyl as a controlled drug, which they did twice in 2021, The Lindesmith Center was a boutique think tank founded to “study issues of individual autonomy and sensible public policy where they clash with popular morals and prejudices.”

1980s & 1990s zero-tolerance drug education — summarized by Just Say No — neglected the sizable portion of people (including teenagers) who just said “maybe”. Hardliners who equated any drug experimentation with the road to ruin lost the public’s buy in. Drug education can’t be effective when it contradicts personal experience. In a perverse twist of bad policy, after 25 years promoting “harm reduction”, we now have absolutely lethal street drugs.

The research center that became the advocacy group Drug Policy Alliance was founded in 1994 by a Princeton University professor named Ethan Nadelmann who left academia with funding provided by George Soros. Soros is — bar none — the paterfamilias of a multigenerational harm reduction effort that’s now being led by his billionaire son, an enthusiastic Democratic donor. Over three decades they have funded hundreds of millions of dollars to drug policy reform.

I learned about DPA (at the time it was called the Lindesmith Center) in 1999, in a class called Cultural, Social & Historical Overview of Chemical Dependency at UC Berkeley. We were told about their upcoming conference in San Francisco, Just Say KNOW: New Directions in Drug Education which I attended on October 29, 1999. Notable speakers included: then Director of the Lindesmith Center, New York, Ethan Nadelmann; then San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown; and then San Francisco Supervisor Gavin Newsom who proclaimed Friday October 29 “Drug Education Day” in honor of the conference.

In a 1998 pamphlet published by Foreign Affairs, the magazine for the Council on Foreign Relations, of which I have a copy, Nadelmann made the case: since drugs are part of society, we have no choice but to learn to live with them so they cost the least possible harm. This was the crux of harm reduction: drugs are part of society, how do we adapt to that reality with the least negative consequences?

Fair question. The answer meant something else when ecstasy was the scariest club drug.

Just Say Know

Under the oversight of a sociologist named Marsha Rosenbaum, director emerita of the San Francisco office of the Drug Policy Alliance, I became the intern from late 1999 through 2000. When he was in town from New York, I did meet Ethan Nadelmann on several occasions. My recollection is a friendly, busy professional neatly dressed in a suit. (He left DPA as an employee in 2017 and has branched into the the e-cigarette industry.)

Marsha Rosenbaum was an early thinker in the drug reform movement. She was an intelligent and persuasive messenger and much of her research involved marijuana policy and evidence-based drug education. The last time I saw her was at a party in a Marin County private home in 2001 or 2002 that was raising awareness for recreational cannabis. It was a purely pot crowd. That crew could not have imagined that street drugs like fentanyl were on the horizon — and that the second guard of DPA would lobby for their access 20 years in the future.

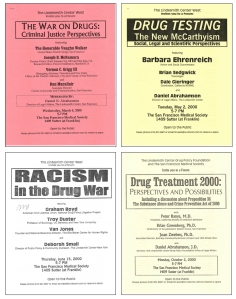

Marsha and her assistant Ellen organized several forums in 2000. The drug reform debate was robust, bipartisan and led by intellectuals and activists from multiple backgrounds.

The Honorable Vaughn Walker, Joseph McNamara, Vernon Grigg, J.D., Dan Macallair, Barbara Ehrenreich, Brian Sedgwick, Dale Gieringer, Daniel Abrahamson, J.D., Graham Boyd, Troy Duster, Van Jones, Deborah Small, J.D., Peter Banys, M.D., Brian Greenberg, Ph.D, Joan Zweben, Ph.D

click to see larger

my background

Drugs interested me from a young age. Some context: I was a kid in counterculture’s cradle. Vestiges of the flower children had left their trippy fug in the social membrane of 1970s San Francisco where I grew up. Unless you were cloistered, you knew about drugs. That said, I definitely leaned in.

Fentanyl has turbocharged the furious remnants of 1960’s drop-out culture, but We’re generations beyond peace and love. The new milieu is not about finding deeper meaning; it’s about losing everything (with a little help from the health department).

In my thirties I pivoted to understanding addiction. Through the lens of addiction medicine, drug reform lit a fire in me. In 2000 I was a campaign speaker supporting DPA-backed Proposition 36, the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act of 2000.

There was NOT consensus supporting this proposed law in the drug treatment world. Many providers were opposed to Prop 36 for fear that any relaxation was going to send the wrong message and fuel addiction. I had what today would have been a “viral” moment with the actor Martin Sheen during a press conference he was speaking at in opposition for that reason.

But the real pushback came from California law enforcement; they were lockstep against it (with the exception of San Francisco DA Terence Hallinan, the OG progressive prosecutor — and the first older Irish boss that Kamala Harris succeeded professionally).

My initial speaking performance was admittedly feeble. From a “debating” standpoint, the seasoned DA in opposition wiped the floor with me.

For me to have spoken about anything publicly, let alone debating a major drug reform law against a DA from the East Bay, was major deal. As a kid, my elementary school had a weekly assembly that included 8th-grade speeches in front of the entire campus. I fretted and palm-sweated over it for months until I realized they went alphabetically and the school year was going to run out before they got to my name. (Saved by a W!) Before this campaign event, at age 32, I’d still never done actual “public speaking”.

He was logic and I was emotion; it wasn’t enough. I realized that in order to be effective I couldn’t just keep repeating “the drug war is bad”. I had to understand in detail what the new law was proposing and why it was necessary. If I was going to be taken seriously by potential voters against professional speakers — and I wanted to be — I had to introduce statistics.

I never went into another debate thinking that moral clarity was an argument. I needed data. (See below.) Later in the campaign when I found that East Bay DA as my opponent again, he was still formidable (but this time he only used me to wipe the counter).

In November of 2000, Proposition 36 won with over 60% of the vote.

lots of Americans got caught up in The 1980s and 1990s drug War but

It must be said that there were elements of full-on racism. Men of color were disproportionately affected by the policing, incarceration and punitive drug policy that was supported by both political parties. For the past 25 years, DPA has spent hundreds of millions of dollars addressing this.

Here’s a snapshot of 2000-era drug war facts from my contemporaneously collected banker’s box

(ie. actual pieces of paper, not the internet.)

Beginning in 1989, the number of drug offenders going to prison exceeded the number of violent prison commitments and continued to grow every year after;

In 1995 only 13% of all state prisoners were violent offenders;

Over 80% of the increase in the federal prison population from 1985 to 1995 was due to drug convictions;

More persons were added to prisons and jails in the 1990s than during any other decade on record;

This increase included a nearly doubling of violent offenders, a tripling of nonviolent offenders and an eleven-fold (1040%) increase in drug offenders;

The number of drug prisoners in California increased over fivefold between 1986 and 1999;

Over 28% of the prison population in California were drug offenders, 12% were being held for simple possession;

Between 1986 -1996, drug commitment rates for Black males ages 15-29 increased six-fold while the comparable rates for young whites doubled, even though surveys showed similar drug usage;

The federal anti-drug budget increased from $4.7 billion in 1988 to $19.2 billion in 1999;

By 2000, nearly one in four persons (23.7%) imprisoned in the United States was imprisoned for a drug offense;

From 1984 to 1996, California built 21 new prisons, and only one new university;

The California Correctional Peace Officer’s Association (CCPOA) — a.k.a. the private prison lobby — was a 28,000 person union with some of the highest paid guards in the industry. Nonviolent drug offenders kept them in business. They were the largest contributor to political campaigns and most powerful lobbying voice in the state;

In 2000, California had twice as many persons incarcerated for drug offenses as its entire 1980 prison population.

compare:

The 1990s drug war was bipartisan

In addition to the drug war fervor that electrified Republicans AND Democrats nationally, California had specific mandatory minimums for drug crimes and the infamous 3 strike sentencing laws. Despite these punitive interventions, a criticism from our side was that drug potency was going up and consumer prices were coming down.

The most important thing to know about prop 36 is that it diverted people from mandatory incarceration into drug treatment by returning sentencing discretion for non-violent, personal use convictions to a judge. The intention of this law was to provide a client-centric offramp from addiction through the supervision of the court and was administered at the county level by the Department of Public Health.

And this was a bold fucking ask from California voters in 2000. It was opposed by Democratic Governor Gray Davis and the Democratic attorney general. It was opposed by Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein. It was supported by the Republican congressman running for her senate seat.

to date (September 2025), the only Republican I’ve ever voted for was Representative Tom Campbell in 2000 because he was more liberal on drug policy than Democrat Dianne Feinstein.

The drug war was practically a standalone economy. Especially in California. But drug reform was not partisan until the shadow party got involved 25 years ago. Now, even for the riskiest users, Democrats are comfortable removing the friction of the court system completely.

Today drugs are stronger, cheaper and more available Than ever

Instead of local bikers cooking the product we have international cartels upending human migration patterns and sowing death and destruction. And drug reform has been simplified into predictable partisan stances, with the right limiting access and the left facilitating it.

Fentanyl and the drugs that are coming are too serious for that. I’m concerned, especially now that the Trump Administration is taking bold action against the cartels, that the left will instinctively double down on whatever they perceive the opposite of that to be. We will need to fight narco-domination as a country.

Forming the following opinion — by championing access as drugs have become stronger, deadlier and more addictive, progressive drug policy has contributed to an increased rate of addiction, which has contributed to a bigger market for the cartels — has cleaved me from the Oregon Democratic Party. My former political teammates are still trying to justify Measure 110 as good law that got a bad rap.

This topic is too known to me to just assume the prescribed shadow party orthodoxy. Strict partisanship can become a mental cage. Thank you, reader, for the chance to rattle out of mine.

In 2000 I wrote about a Seattle conference addressing an uptick in fatal heroin overdose. There was urgency to tackle a crisis that in 1997 was responsible for the death of under 5,000 people a year. Today over 5,000 people A MONTH die from opioid poisoning.